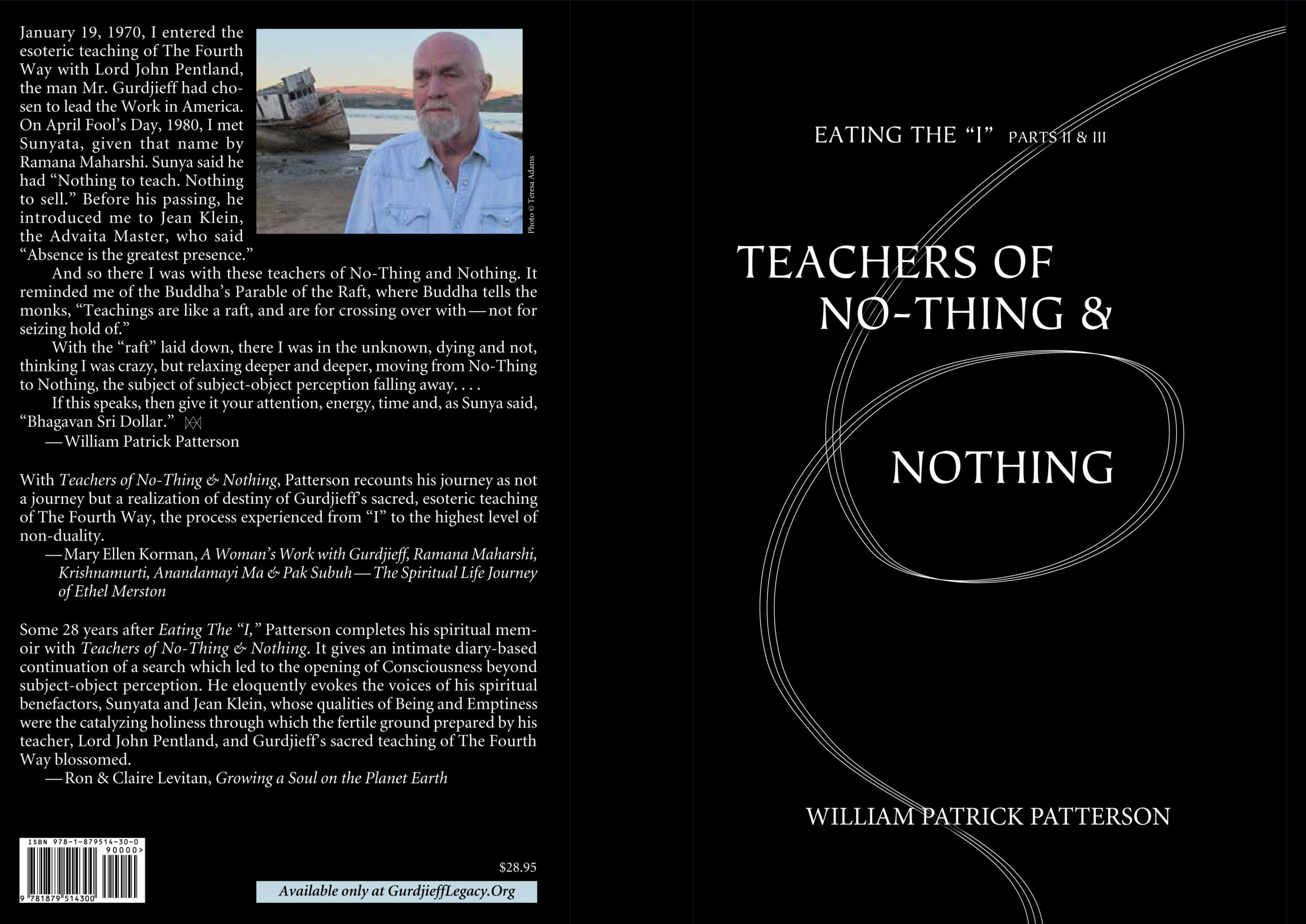

Mary Ellen Korman, Author,

A Woman’s Work with Gurdjieff, Ramana Maharshi, Krishnamurti, Anandamayi Ma & Pak Subuh—The Spiritual Life Journey of Ethel Merston

“With

Teachers of No-Thing & Nothing, Patterson recounts his journey as not a journey but a realization of destiny of Gurdjieff’s sacred, esoteric teaching of The Fourth Way, the process experienced from “I” to the highest level of non-duality.”

Ron & Claire Levitan, Authors,

Growing a Soul on the Planet Earth

“Some 28 years after

Eating The “I,” Patterson completes his spiritual memoir with

Teachers of No-Thing & Nothing. It gives an intimate diary-based continuation of a search which led to the opening of Consciousness beyond subject-object perception. He eloquently evokes the voices of his spiritual benefactors, Sunyata and Jean Klein, whose qualities of Being and Emptiness were the catalyzing holiness through which the fertile ground prepared by his teacher, Lord John Pentland, and Gurdjieff’s sacred teaching of The Fourth Way blossomed.”

A Fourth Way Teaching Book Itself on Many Levels

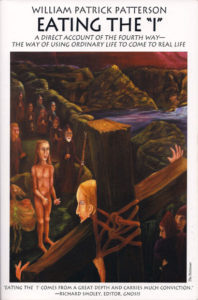

IT’S NOT A MYSTERY what happened after

Eating The “I”, Part I, or those of us actively engaged under the guiding direction of Fourth Way teacher William Patrick Patterson for we are the recipients of that Work. For others having read at the end of

Part I that the author left the New York Gurdjieff Foundation must naturally create a question.

Patterson’s most recent three decades have produced a serious and significant body of work, including ten books, along with eight films, four of them filmed on location in Armenia, Georgia, Turkey, Egypt, Russia, France and England—and all focused on Mr. Gurdjieff and The Fourth Way teaching. But what exactly happened following the end of

Eating The “I” and that period that begins these past three decades—of unflagging efforts and undeterred pace—that gave birth to such a profound legacy, inclusive of leading Fourth Way Groups, taking the role of teacher, giving talks, seminars, retreats, as well as founding and editing

The Gurdjieff Journal while

simultaneously writing books and producing films?

This tenth book,

Teachers of No-Thing & Nothing, Parts II & III, an intriguing and revealing title, is not only a surprising response to this question but a deeply moving one. A spiritual autobiography and continuation of

Part I—yes—but written in an uncommon style: chronological

diary entries that include teaching dialogues from his two nondualism teachers (hence Parts

II & III ), who Patterson refers to as his Benefactors: Sunyata, the Danish “rare-born mystic,” given the name by the Sage Ramana Maharshi, and Jean Klein, the French medical doctor—both from the Advaita Vedanta Tradition.

Patterson couldn’t have known at the time that he left the organized Work in October 1981 that his teacher, Lord Pentland, would leave the body a little over two years later in February 1984. And yet we hear, through Patterson’s recounting of dreams, that for years afterward Lord Pentland would continue to speak to him, indicating the depth of their bond. What can now be seen as his introduction into the teaching of nondualism had already begun in April 1980 when he met Sunyata and heard him state in his simple manner, “The witness is a high state, but it’s only a state.” For Patterson, this was a new awakening—a catalyzing shock reflecting back to him in recognition that

this is where one is.

His inner work thus far had brought him to the state of the Witness, one of conscious attention and inner emptiness. But don’t we all believe that our attention is already conscious

and consciously being directed? To understand what the

Witness represents, we simply need to return to the body-mind sensation, self-observe and verify for ourselves that the ordinary state of attention is a mechanical oscillation between subject or object. That is, we are either

all subject, me-myself-and-“I”, or,

all object, the attention projected outwards onto the world of objects, sentient or not. So, the impressions received are necessarily limited and

partial. For the Witness, on the other hand, the weight of attention is grounded in

Being, and comes to fruition only when the body-mind has digested the food of Work-on-oneself to a living inner emptiness and stillness. Only then, can the simultaneous subject-object Witnessing occur and its nature is the fullness of impartial perceiving.

Although similar to Part I, which presents the life story in vivid and revealing form, Parts II & III provide an illustration into the process of awakening—seeing, dropping and going beyond the person—but now from within a new context of deeper discrimination and impartiality—that of the Witness. The one writing and reporting on “Patterson” is possible only because he has gone beyond “him.” It is rare enough to read a spiritual autobiography, and rarer still, one rooted in The Fourth Way, by “a man who takes on himself the role of teacher.” [Emphasis added.] But Patterson does not obfuscate the quintessential problem to liberation: the person—no matter how rarefied the “I” that must be consciously eaten.

Through Sunyata, Patterson was availed of the beginning contact that would bridge the gap between the Work understanding of the many “I”s through to the Witness, and a forefeeling of the response to his own question as he states it, “…the perspective of duality no matter how refined did not answer the essential question I had been carrying all these years—what is the self in self-sensing, self-remembering, self-observation?” Although not formulated or assimilated at this point, Patterson is opened to a new awaring that the self in his question lies beyond the Witness.

The book provides a succinct life-story of Sunyata, born Alfred Emmanuel Sorensen, as well as numerous and delightful exchanges, events, happenings and one-to-one experiences with him. A number of darshans that Sunyata offered are colorfully portrayed, giving a taste of the many and varied seekers who attended—none of them resembling the types encountered previously in Gurdjieff groups he had attended starting in January 1970 when he first entered The Work. So different, in fact, that Patterson’s first impression of them was that they “looked to be mostly low-lifers to no-lifers, their questions the usual safe ‘spiritual’ ones.”

“Sunya had no teaching,” Patterson says, “In fact, mention the word and he would laugh.” But the full immersion into this “no teaching” began when Sunyata, whose name signifies full, solid emptiness, moved in with Patterson and family in May 1982. Faced with Sunyata’s eternal ocean of Emptiness was crushing to “Patterson,” the person, and he says, “It is one thing to see your teacher at a group meeting or Work day or having made an appointment, and quite another when exhausted and angry from the day’s events and there is Mr. Nobody in all his ‘full, solid emptiness.’ You are completely full of the day, he is just the same as when you left him in the morning, having brought his tea and toast to his bedroom, in a word—empty.”

But months later, Patterson understands, no longer as an idea, Gurdjieff’s statement, “The last thing a man will give up is his suffering.” To be in the presence of emptiness was to have reflected back the unending person-dance, until at last the parade simply begins to recede into the ground of Being, which he must continually reaffirm, assimilating this wordless teaching, until, as he says, “A simple quiet clarity strikes through all your centers—suffering is a choice.” This is a taste of the realizations he would come to while living in the presence of this awakened Mr. Nobody, who among the many sages he encountered, received the radiance of Ramana Maharshi three different times and who in 1984 left his body at the age of 93.

It was Sunyata who in December 1981 gave Patterson Advaita Master Jean Klein’s book Neither This Nor That, I Am, and introduced them in April 1982. While both Sunyata and Klein are representatives of the Advaita Vedanta Tradition, Klein had also studied a specialized yoga in the line of Kashmiri Shaivism, also a nondualist Tradition but differing with Advaita in its approach, although in essence not contradictory. Advaita regards the phenomenal objective world as an appearance within Consciousness, that is, it’s an illusion, Brahman alone is Real; Kashmiri Shaivism, on the other hand, regards the phenomenal objective world as real and as One with the Universal Subject, appearing separate only from the point of view of limited subjects.

This second approach, transmitted through Klein, seems to have given a certain ground to Sunyata’s Ocean of Emptiness—one that embraced Gurdjieff’s teachings on Unity, the Law of Seven, Law of Three and the Ray of Creation, as echoed in his statement, “Matter or substance necessarily presupposes the existence of force or energy. This does not mean that a dualistic conception of the world is necessary. The concepts of matter and force are as relative as everything else. In the Absolute, where all is one, matter and force are also one.”

With Jean Klein, Part III, the journey that had begun with Sunyata deepens. A vastly outwardly different representation of the nondualism Tradition, Klein had been a medical doctor, spoke four languages and as Patterson says of his initial impression, “spoke in a precise, intellectual manner.” Klein tells him during their first meeting, “You are tired of the phenomenal.” And as with Sunyata pointing out the Witness, Klein had shone a beam of clarity into his inner experiencing—the answer to liberation is not to be found in the phenomenal world of objects—not even refined objects.

Other than the scheduled week-long retreats and seminars throughout the year, there were no set ongoing meetings or darshans with Jean Klein. One gets the impression that Klein divided his time between Europe and the U.S., and so to study with him, one had to actively seek him out. As senior editor of a business magazine, Patterson often intentionally created business trips in order to see and be with Klein and soon began to help in the organizing of meetings and seminars.

Patterson is now being introduced to and immersed in a nondual teaching of Being by way of a special energy-body yoga that as Jean Klein told him, “is a pretext for sharing the Silence.” Diary entries in this beginning period with Klein give the sense of two inner workings occurring—on the one hand a continuing exploration in opening to Being and Silence through the special energy-body yoga, releasing and emptying in the midst of shocks, while on the other hand the activity of a strong “doer,” as though a demand, to make something happen for transformation to take place. But not to be lost on the reader: Patterson puts on display his “Patterson”—and how many of us could and would do that? We see and hear “his” wanting “knowledge,” the various ways “he” manifests, and the karmic incident “he” carries since childhood.

Observing in himself this drive for knowledge, he says, “Each time spiritual knowledge has been my spur.” But soon after, given his steadfast sincerity, factually accepting and admitting his experiencing, he comes to real questions and Klein responds, giving Patterson one of the most beautiful and luminous transmissions of Truth regarding Subject-Object Relationship. With respect to understanding, Klein tells him, “The real expression would be to be ‘awakened in consciousness.’ You must know it. But this ‘knowing’ is not a thought-form.”

When Patterson first met Sunyata he had already come to what Sunyata called the “high state” of the Witness where the perceiving is true subject-object. Eight years later, after waiting four days for a private meeting, Klein tells Patterson, “You have the geometric understanding,” meaning, as Patterson says, that he had “the intellectual and emotional understanding of the teaching but had not fully experienced it” and that this quality of understanding “is a higher reasoning, one that leads beyond objects to the ultimate subject.” In one of his dialogues, Klein expounds on the meaning:

On the level of the mind, ordinary understanding, the nearest we can come to objectless truth is a clear perspective, a vision of the objectless. I often call this a geometrical representation. The contents of this representation are what could be called the facts of truth: that the mind has limits; that truth is beyond the mind; that truth, our real nature, cannot be objectified, just as the eye cannot see itself seeing; that truth, consciousness, was never born and will never die; that it is the light in which all happenings, all objects, appear and disappear; that in order for there to be understanding of truth, all representation must dissolve. When this representation, the last of the conventional subject-object understanding, dies, it dissolves in its source—the light of which the mind informed but could not comprehend. In other words, understanding dissolves in being understanding. We no longer understand, we are the understanding. This switchover is a sudden, dramatic moment when we are ejected into the timeless.

Having actualized the geometric understanding, Patterson later comes to the experiencing of “the gradient between the waking state and the subconscious lessening to the degree that the former is assimilated in the latter”—this is what Klein called, “the Blank state.” Patterson describes it as “still in subject-object perception but where there was very little subject.” Then, four years later, he is imprinted in the

Being Reality that Klein, Sunyata, Lord Pentland and Gurdjieff had all been pointing towards. That is, he suddenly experiences

pure Consciousness, beyond subject-object. As he says, “…

suddenly there was no subject. There was no perceiver, no thought. Only perceiving—direct, global conscious perception-reception of what is present without referent to past or future.”

“What was experienced,” Patterson recognizes, “was

Turiya, the fourth state of the Self…” And, it is what five years earlier Klein had been speaking to when he told him:

The moment there is a “watching” that projects energy in space and time there is taking, attaining, grasping. It is an activity whose source is memory, not being. But the moment you welcome the perception, you are in the receiving position and projection dissolves completely. And, suddenly, you are taken by your own presence (which is not a subject-object relationship)…. It is the point of being completely free of all volition, personal volition. You are really a channel.

This realization of the transmission—

Turiya—was the response to his question: “…what is the

self in self-sensing, self-remembering, self-observation?” Gurdjieff could have easily said “sensing,” “remembering,” “observing,” so why, “self”? …In his inimitable way, Gurdjieff buries the clue in plain sight.

What can be so easily missed, given the format of diary entries in which Patterson is not narrating an interpretation of the lived experiencing, is that during the period from 1979 through 1989, Patterson had gone through

five rewrites of

Eating The “I”. At the time, obviously, there was no “

Part I” as a subtitle. So while

Teachers of No-Thing and Nothing is about Sunyata and Jean Klein, it is deeply about the silent current of his spiritual roots in The Gurdjieff Work, occurring simultaneously as punctuated by the appearance of Lord Pentland in dreams along with the conscious and intentional writing of

Eating The “I”— “wishing and willing,” as he says, “to get as close to the bone of the truth as possible.”

While the rational mind expects and even demands neat, straight lines in life, Patterson writes of the new direction his journey would take beginning with his “Charles Fort” dream in 1975 where Lord Pentland hands him an envelope containing a white card inscribed in calligraphy telling him, “It’s one of the original invitations.”; it is fated that he must leave the organized Work. Could it be he was being prepared since Lord Pentland would leave the body in 1984?… “Transmission,” Klein told him, “doesn’t mean doctrine. It is not the doctrine that is transmitted, but the Truth, the Truth of reality. Tradition in the real sense is That which is transmitted from one who knows, who is the Truth, to another who is also . . . but has yet to realize it.”

Beyond the personal story of a teacher in The Gurdjieff Tradition, however, is something else of serious import regarding the deep message of this book as it relates to The Gurdjieff Work itself. If we consider the spiritual idea of

being called, what is the context within which Patterson publishes

Eating The “I” and begins these past three decades reconnecting the roots of Gurdjieff’s sacred teaching of The Fourth Way?

The Gurdjieff narrative that had formed from the 1970s and 1980s was largely being defined in the

public arena through a proliferation of faux Gurdjieff groups, communities, and Enneagram “scholars” putting forth concoctions met by a simultaneous New Age wave of young adults yearning with spiritual hunger. Even within established, authentic Foundation groups could be heard the incorrect notion in using the expression, “Gurdjieff-Ouspensky Work.” Not only did these errors, deviations and distortions require correction but the great need for the wholeness of The Fourth Way teaching

called for its expression reconnecting it back to its source:

Gurdjieff

Sri Anirvan, the Bengali Master and Vedic scholar, once told his student Lizelle Reymond, who later became Madame de Salzmann’s student:

All life is from the Void…. The Void is the matrix of universal energy. One has access to it by four stages. The first stage is to realize the plurality of ‘I’s; the second stage is the recognition of a single ‘I’; the third, is no ‘I’; and finally the Void. Uspenskii speaks about the first two stages in Search of the Miraculous. He remained silent about the last two because he had left Gurdjieff. The writings of Gurdjieff [All & Everything] open for us the frontiers of the two last stages. These are cleverly hidden in his mythical narrations.

But for those with a sincere Wish to awaken, the deep and great scale of Gurdjieff’s teaching, accessible by the four stages, no longer remains a mystery or hidden. The real title of Gurdjieff’s

Legominism, as Patterson reveals, is:

ALL & Everything & No-Thing & Nothing

—Teresa Adams